So this past week we learned that the much-awaited Telegram Open Network, or TON, has failed to launch and will be retired. Telegram creator Pavel Durov wrote a postmortem about it, in which he compared TON to gold and the issuing company’s activities to a goldmine:

Telegram had raised nearly $2 Billion in what was the largest ICO to date in 2018. This was done in an invite-only private sale to accredited investors each investing $1M minimum. They even filed Form D documents with the SEC. So what was the problem?

It seems, from following the proceedings, that the problem was actually quite straightforward, quite fundamental, and common to many crypto projects. Namely, the same token that was sold in the ICO (and treated as a security) was subsequently designed to be used as a currency between regular, non-accredited investors. Consider this:

In Telegram’s view, that meant that because Gram tokens were exclusively sold to accredited investors, the offering was not required to be registered with or qualified by the SEC. Since then, the company has publically emphasized that Grams should not be associated with expectations for profits based on purchase or holding of the token, essentially implying that they do not constitute securities. Regulators oppose this argument. In contrast, it stresses that once the Gram tokens are released, their purchasers and Telegram “will be able to sell billions of Grams into U.S. markets,” and, therefore, continue the unregistered token sale.

At the very least, something like a Reg A+ “Mini IPO” offering could be done, or for something as large as TON, a regular IPO. But, that would subject the tokens to an infrastructure of brokers and regulated exchanges that are designed for securities trades, not everyday purchases.

A Fundamental Contradiction

This isn’t just an academic discussion about how terrible regulators are. It actually arises from a fundamental contradiction. People buying securities hope to see them go up in price before they sell them to others. But on the other hand, money is designed to be spent, and participants in the supply chain want it to act as a stablecoin pegged to a fiat currency like USD. How can something both increase in price and stay the same price? It can’t.

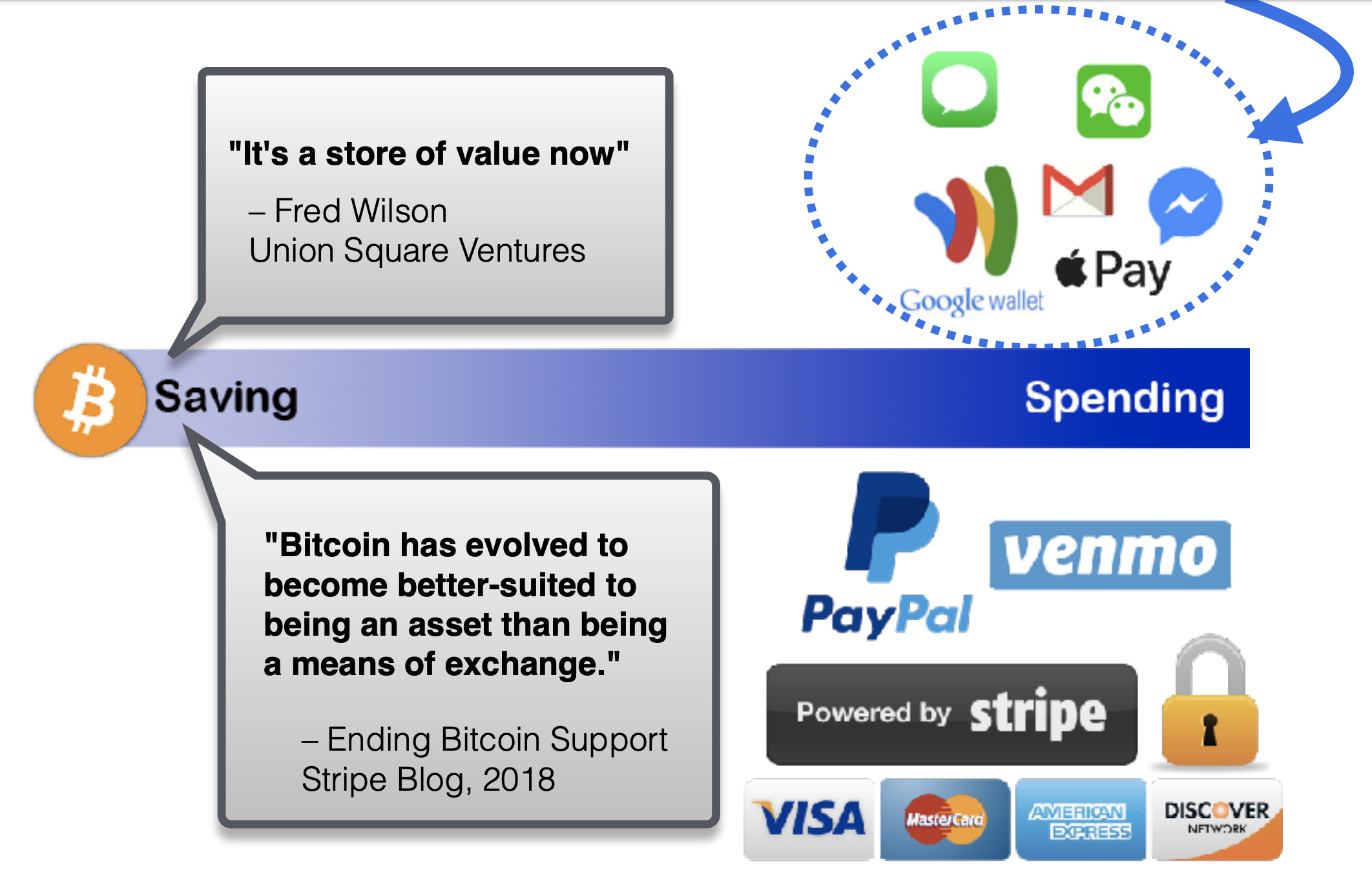

This is the same problem that made the Bitcoin community switch from Satoshi’s original vision of a “peer to peer electronic cash system” to becoming a “store of value and a digital gold”. If you knew each Bitcoin would go from being worth less than a penny to $9,000, would you ever spend them on a pizza? Or anything else?

Let’s not forget, the original promise of crypto was to let open source projects sell tokens to the users, so the network could be owned by the participants. This has dropped by the wayside, for two reasons:

-

The technological reason is that global blockchains can’t scale to handle the number of payments that a real “money instrument” requires. (Kik Messenger and Cryptokitties are two great examples of this, both launched on Ethereum and have been struggling to solve scalability.)

-

The economic reason is that you can’t have the same currency both go up in price and at the same time gain widespread adoption as a means of exchange. Both USV and Stripe realized this about Bitcoin:

How Intercoin Solves This

One of the original design decisions in Intercoin was to separate the payment network into a a global “Intercoin” and “local coins”, similar to how there is an “Internet” and local networks.

As a result, the ITR tokens that are being pre-sold in our current offering are treated like any other securities. We openly tell investors how ITR is designed to increase in price as we execute on our roadmap, develop, launch, get the word out, and as more communities buy ITR. If things go as planned, the investors are front-running the various organizations (including universities, conferences, festivals, congregations, etc.), who will be purchasing ITR from them later on, to be exchanged 1-1 with Intercoins.

Moreover, the organizations that buy Intercoins will have to pass AML and KYC, to make sure they’re not, for example, a money laundering front for the Sinaloa cartel or ISIS. On the other hand, regular end-users will never have to hold Intercoins tokens. That is the key. Instead, their wallets will be able to store Casino Chips and NewYorkCoins and ParisCoins and RayBariPizzeriaCoins and MovieCoins and PoetCoins and YangGangUBICoins or whatever else, each of which is pegged to a stable outside currency so no reasonable person would expect to profit from holding them. New projects can be started and fundraise without worrying about the currency in which the funds are raised dropping like a stone.

To make an analogy with the regular Internet we are familiar with, requiring everyone to use the main token in everyday transactions is like requiring every end-user to have a Tier 1 connection to the backbone of the Internet. (This gets even worse when every full node has to store everything.) On the other hand, separating the main coin from the local coins, as Intercoin does, is like having people get on their local coffee shop’s wifi, and let the coffee shop worry about maintaining a fast connection to the Internet, licenses for installing the cables, and so on. It’s no wonder regulators are much happier with such a framework, because compliance can be done by the “big boys” while regular people can go from one coffee shop to another and use small amounts of bandwidth/currency/etc.

Dealing With The Reality

This showdown with regulators has been played out over and over, and is why crypto startups must be careful stepping on the same rake over and over. Kik Messenger had faced similar problems after selling its KIN tokens. The Canadian company was also prevented by the SEC from going forward with KIN, even though it arguably already had a currency being used inside its messenger. The fight nearly ended their main messenger app:

Among all the social messaging and communication companies, Telegram ranks very highly when it comes to its focus on preserving people’s freedom and privacy. Its founder, Pavel Durov, founded Vkontakte (the Russian Facebook) but sold his shares and fled the country when the government and Mail.ru group began muscling in.

With a strong libertarian streak, the Durov brothers took $300M from selling the VK shares and started Telegram. They hired many talented cryptographers, invented their own techniques, offered bounties to anyone who can break the encryption, and so on.

With this kind of pedigree, TON network had a ton (pun intended) of promise and potential. It was open sourced and is now in the process of being launched by a decentralized community. Given the criteria the SEC has established to no longer consider ETH to be a security, this may be enough for the TON network to actually work – and for the tokens to eventually be sold.

Conclusion

If you raise funds offering an asset that people hope will go up in value, don’t expect to use this same asset as a currency later on and get mass adoption. You’ll face scrutiny not just from the SEC, but also FINRA, FINCEN and communities all around the world who are concerned about things as simple as capital flight. There are essentially two options:

-

Open source your code, step away and let your decentralized community run it, as was the case with Bitcoin, Ethereum, and now possibly TON. Perhaps one day the original investors can sell their tokens, and anything else will be too decentralized to enforce.

-

Make a two-tier system, and resolve the inherent contradictions of using the same asset to both invest and spend money. Intercoin takes this second approach, which hopefully will help normalize relations with towns and countries. Regulators aren’t just being assholes, there are underlying reasons for the laws they interpret.

In order to gain wide adoption, a cryptocurrency must be architected to solve the challenges of scalability, liquidity, and regulations. That is what Intercoin was launched to do. If we don’t do this, then the world of payments will belong to Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc. and we’ll just live in that Feudal world, as we already currently do.